[Photo credit: NC FIELD]

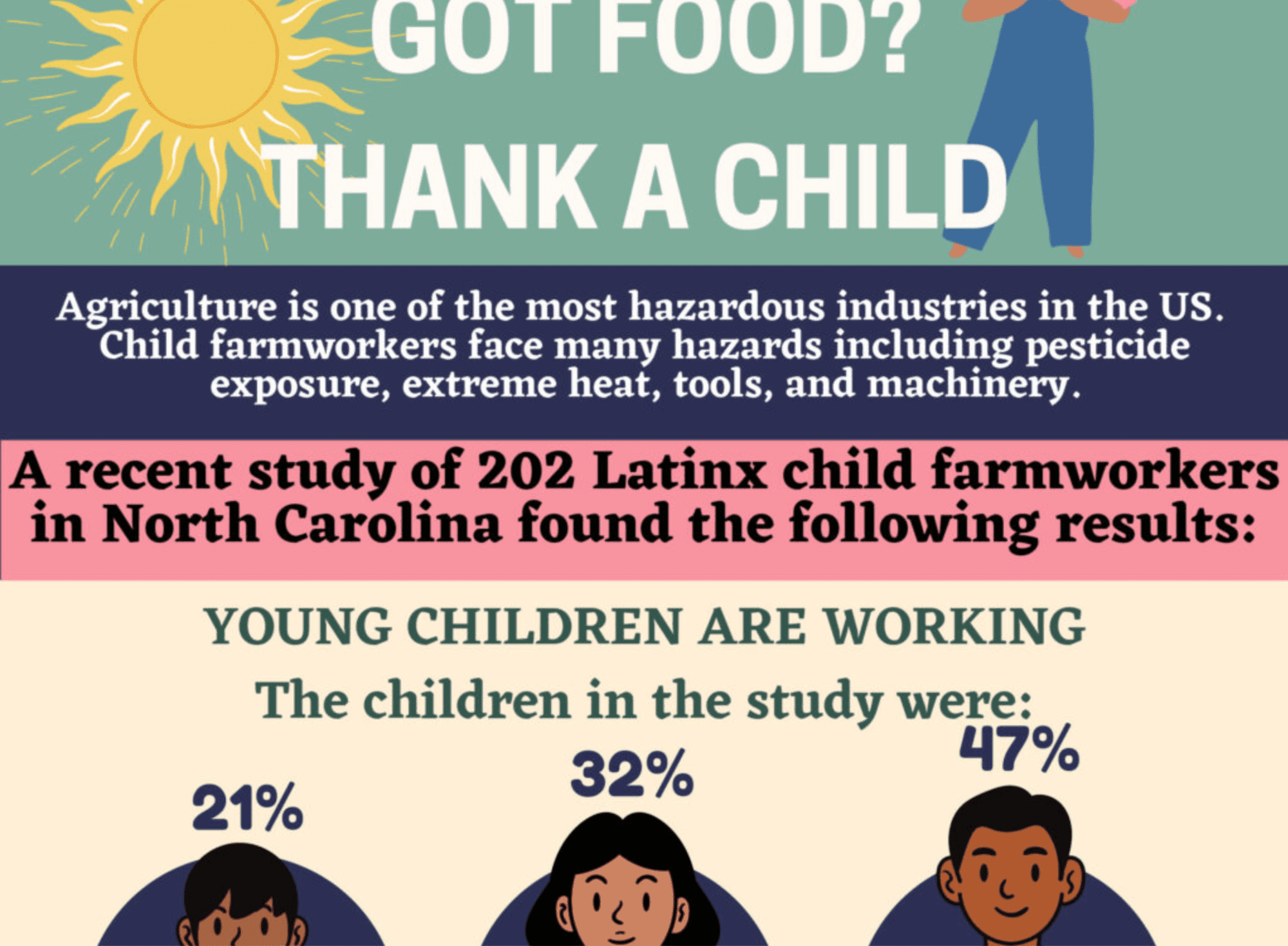

When you buy a box of blueberries at the grocery store, how often do you think about the people who picked it for you? In North Carolina, blueberries, tomatoes, sweet potatoes and other crops can be harvested by child farmworkers as young as 10 years old – and federal law permits it. Recently, North Carolina research partners carried out the Hired Child Farmworker Study, examining the health and safety of hired Latinx child farmworkers. What we found paints a surprising picture of the characteristics of child farm labor in North Carolina, and the need for policies that protect child farmworkers from injury and support their education.

Who are the children working in the fields?

In 2017, our research team interviewed 202 Latinx child farmworkers across 20 North Carolina counties. Most of these children – boys and girls – were born in the United States to immigrant parents, but a few were immigrants themselves. Over half were aged 10-15, and the rest were aged 16 or 17. These children included both seasonal workers, who live in North Carolina year-round, and migrant workers, who move from state-to-state to do farm work.

This infographic on the research findings was created by youth research partners from Student Action with Farmworkers’ Levante Leadership Institute (click to see the full-sized infographic):

Impacts on education

Farmworker children face educational barriers that differ from those faced by most other youth, including conflicts between school and work schedules, language barriers, transportation issues, navigating unfamiliar school systems, and moving frequently for work.

Almost one-third of the child farmworkers we interviewed had repeated a grade during their education. This is three and a half times higher than the statewide average rate of about 8 percent. Twice as many migrant child farmworkers had repeated a grade compared to seasonal workers (50% vs. 26%).

Injuries on the job

Agriculture ranks as one of the most dangerous industries in the United States. Hazards include machinery, high temperatures, sharp tools, and chemical exposure. For children, whose bodies and brains are still developing, hazardous exposures could result in immediate or long-term harm. In our study, two-thirds of children reported experiencing an injury while working in farm work.

Heat-related illnesses are a significant concern. These range from minor heat rash all the way to heat stroke, which is life threatening. Nearly half of the children we interviewed had experienced at least one heat-related illness symptom.

“Well, if they’re rushing you, then you will feel stressed out. It’s like, you need a break, or you’ll pass out or something” – Sixteen year-old tobacco worker

Exploitative practices

Exploitative practices can operate relatively unseen in the agricultural work environment. In some ways, they are built into the law itself – for example, agricultural workers are exempt from overtime pay laws.

- Over a third of the children in our study had worked more than 40 hours a week.

- Another third of the children were paid a piece-rate (only paid for the number of buckets they harvest), which can increase risk of injury and exploitation.

- Nearly all of the children in the study were paid in cash, which makes it easy for supervisors to underpay them.

Overall, child workers may be less likely than adults to speak up against dangerous, unfair, or hostile work environments, which increases their vulnerability to exploitation and injury.

Policy Recommendations

Hired child farmworkers experience educational disruptions, hazardous conditions, injuries, and are likely more vulnerable to exploitation than adults. As a result, the research partners recommend several steps to improve health and safety outcomes for child farmworkers:

- Congress and the US Department of Labor should re-evaluate agricultural exemptions from child labor laws in the context of 21st century agriculture. These laws date back to the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938. Doing so would promote more dialogue about whether and how to apply the same child labor protections to agriculture as exist in every other industry.

- The NC Department of Labor should better enforce existing safety laws and standards in order to better protect child workers.

- Several state and federal agencies conduct educational programs that serve farmworker families. These should be properly funded in order to meet the unique needs of this population.

- Congress should consider larger, more comprehensive reforms, including immigration reform and living wages for farmworkers. These would address some of the root causes of agricultural child labor.

Next time you pick up a tomato in the grocery store, consider the hands—possibly a child’s—that picked it. If you want to get involved in efforts to ensure protections for children, several local and national organizations are working on addressing agricultural child labor. These include: Student Action with Farmworkers, NC FIELD, Association of Farmworker Opportunity Programs (AFOP), and the Child Labor Coalition.

Taylor Arnold is project manager for the Hired Child Farmworker Study that brought together researchers from Wake Forest School of Medicine, East Carolina University, Student Action with Farmworkers, and community members.