After years of steady decrease, North Carolina’s infant mortality rate went up for the second year in a row.

By Rose Hoban

More North Carolina newborns died in their first year of life last year, as the state’s infant mortality rate ticked up for the second year in a row.

In 2012, of every 1,000 live births, 7.4 babies under a year old died. That’s an increase from an all-time low rate of 7.0 infant deaths per 1,000 live births in 2010; the 2011 rate was 7.2.

The North Carolina State Center for Health Statisticsrecorded 119,767 live births in 2012.

“It’s discouraging that the rate worsened, particularly after the past several years, where we were at record lows,” said pediatrician Peter Morris, who heads the legislative Child Fatality Task Force.

He said he hoped the uptick was a statistical anomaly and that the overall five-year rates would show a more favorable trend.

Morris noted that deaths from sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) were down from 50 in 2011 to 28 in 2012, even as the overall rate increased.

“But the disturbing trend over the past three years is that our infant mortality rate is getting worse, and the gap between whites and blacks is getting worse,” he said.

Stubbornly high

When the Child Fatality Task Force was founded in 1991, the state had the highest infant mortality rate in the country and one of the highest rates of death for children under 17.

Since that time, Morris said, the rate of death for all children under the age of 17 has fallen in North Carolina by almost half, and the infant mortality rate has fallen from 10.9 deaths per 1,000 live births to where it is today.

But other states have also worked on reducing infant and child deaths, and North Carolina’s infant mortality rate has consistently been among the 10 worst in the country.

But Morris said his biggest concern is the persistent difference in infant mortality between whites and blacks.

Last year, that gap widened, with infant mortality rising more in African-Americans, from 12.9 to 13.9 deaths per 1,000, while the rate for whites stayed the same, at 5.5 per 1,000. Morris noted that the infant mortality rate for Latinos is similar to that of whites, and dropped this year.

Poverty is associated with infant mortality, Morris said. But he said poverty and education levels don’t explain the difference in infant mortality between whites and blacks.

“There’s a similarly high infant mortality rate in educated African-American women,” Morris said.

He said that, ironically, one of the best ways to ensure better birth outcomes is by increasing access to birth control for women, allowing them to space their pregnancies.

The data also showed that about half of the women who gave birth in 2012 were overweight or obese, which can increase the risk for health problems in their infants.

Morris also noted that the research indicates that the state of a woman’s health before she gets pregnant is a prime predictor of how healthy her babies will be. About 12 percent of births were to women who had fewer than six months between delivery and a subsequent conception.

“If you’re trying to take care of women’s health before they’re pregnant, it’d be a really good idea to have health care coverage for their entire adulthood,” Morris said.

Even though low-income women are eligible for Medicaid when they’re pregnant and for three months after they give birth, about one in five of North Carolina’s adults under the age of 65 is uninsured.

“I think the persistent racial disparity in infant mortality is disgraceful, and as a state we need to make a concerted effort to make that disparity go away,” said Rob Thompson, head of the Covenant with North Carolina’s Children, an advocacy group.

“In some ways, while disturbing, it’s not necessarily surprising, given how hard hit rural minority communities have been by the recession,” Thompson said. He also cited state and local budget cuts to health care and human services.

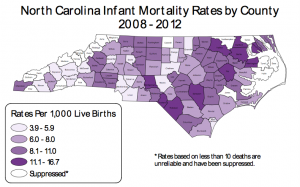

Most of the highest rates of infant death are in rural counties. In Pasquotank County, for example, the rate was at 20.4 deaths per 1,000, the highest in the state.

Infant homicide up

For Tom Vitaglione, the most concerning number in this year’s report is the uptick in the number of infant homicides.

“Infant homicides are always worrisome,” said Vitaglione, who works with Action for Children North Carolina. Through the 1990s, he said, the state regularly had more than a dozen infant homicides a year. But over time, that number fell, decreasing to six or seven a year.

“We’d been doing a lot of work to address domestic violence,” Vitaglione said. “In 2010, there were only two infant homicides.”

So last year’s 11 infant homicides came as a surprise.

Vitaglione noted that medical examiners and law-enforcement officials have been trained to recognize incidents such as accidental smothering and are less likely to label an infant death as SIDS rather than something more suspicious.

As a result, he said, a death listed as a homicide is more likely to be a homicide.

“It could turn out to be a statistical anomaly or it could be something bad,” Vitaglione said. “The economy is down, the pressure on families is terrible.

Vitaglione said that some people might suggest waiting another year to see what the 2013 statistics show, but he disagrees with that stance.

“If something bad is going on, we need to know,” he said.