By Nancy McLaughlin

Greensboro News & Record

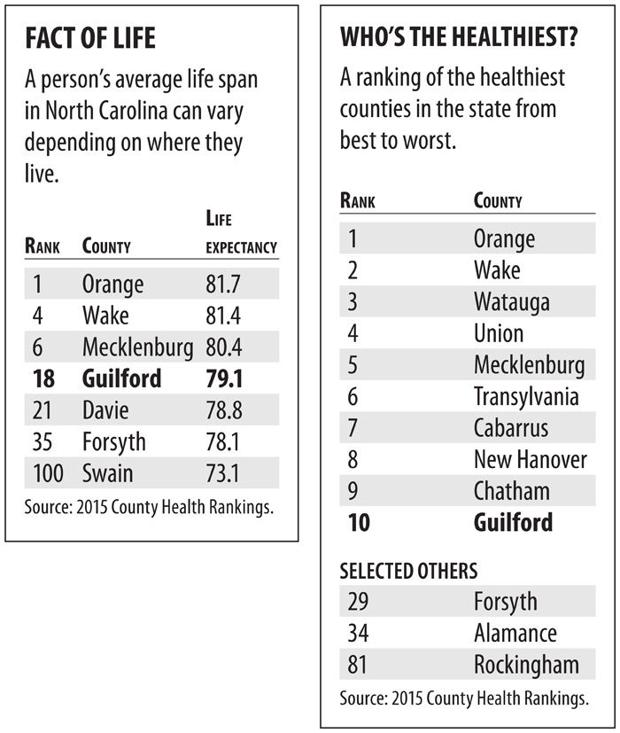

In Watauga County, residents can expect to live an average of 81 years — on par with Japan, where people have the longest life expectancy of any major country.

Drive 140 miles southwest to Swain County and a person’s life expectancy declines by nearly a decade to 73 years.

Then there’s Guilford County where residents can enjoy a life expectancy of 79 years, while in Rockingham County it’s 76 years — the lowest in the Piedmont Triad.

In North Carolina, how long you live can come down to one thing: your ZIP code.

So says a new report by the advocacy group NC Child, which looked at the well-being of children in the state.

Laila A. Bell, the research and data director for the nonprofit, compiled the study based on social, economic and health outcomes as a supplement to the annual North Carolina Child Health Report Card. She said the disparities between counties reflect a myriad of factors.

“Things like income and education, access to healthy food and access to medical care are all kind of rolled up in that number,” Bell said.

Guilford County fared better than other counties in a number of categories. Fewer of its residents are in the “poor or fair” health category compared to the state average. Guilford also was above the state average in obesity and pollution.

However, in Rockingham County, a higher number of residents fit in the “poor or fair” health category compared to the state average. More of its residents are smokers, overweight and lack physical activity than much of the state, according to the report.

Overall, North Carolina has some of the wealthiest pockets in the nation. But at least one in four children live in poverty and research shows children who are raised in poverty are more likely to suffer from acute and chronic health problems as they age.

Bell points to other factors that make a difference in the life expectancy of state residents. For example, 1 in 15 births are to a mother who received very late or no prenatal care.

One in 11 babies are born at a low birth weight, putting them at greater risk for future health complications.

Also, 595,240 children are estimated to be living in households that struggle to provide enough healthy, nutritious food for all members of the family.

Bell said the drop in the statewide infant mortality rate, which declined from 10 deaths for 1,000 births to 8.6 deaths, shows what happens when communities make the health of their residents a priority.

“We’ve seen lots of intentional investment at the state and community level,” Bell said. “It also shows what can happen when policymakers and communities work together.”