By Rachel Herzog

NC Health News

The health of kids in North Carolina has improved over time and they’re also doing better in school. But many children live in families struggling to recover from the economic downturn in 2009.

That’s according to the annual Annie E. Casey Foundation KIDS COUNT Data Book, a report on state and national trends in child well-being released on Monday.

North Carolina placed 35th in overall child well-being, according to the report, which looked at trends between 2008 and 2013. The state ranked in the lower half of all states in the four categories measured: economic well-being, education, health and family and community.

While the state saw improvement in indicators for child health and education, North Carolina kids are worse off economically, a change that could lead to negative health impacts overall.

“Despite what’s been a modest economic recovery in the state, our children and families are really being left behind,” said Laila Bell, NC Child’s director of research and data.

Insuring health

In 2013, North Carolina hit its lowest recorded percentage of children without health insurance. Six percent of children in the state were uninsured, a drop from 10 percent in 2008.

“If children have access to health insurance and they’re receiving their preventative care, they’re more likely to maintain a good health status over time, and it affects a lot of other indicators,” Bell said.

Bell attributed the increase in ranking to sustained investments in the state child health insurance program, North Carolina Health Choice, and Medicaid. Combined, these two programs cover more than half of the state’s children.

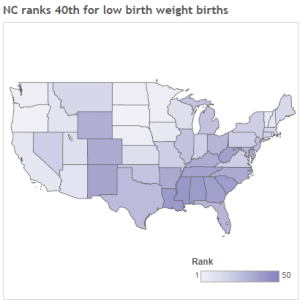

The percentage of low birth-weight babies decreased slightly, but was still one of the highest rates in the U.S at 8.8 percent, or 10,432 babies.

When babies are born with a low birth weight, prematurely or not, they are at risk of health problems later in life, according to N.C. Pediatric Society Executive Director Elizabeth Hudgins. The cause can be any of a variety of factors, including prenatal care, the mother’s health and the health of the community.

“It’s a good overall indicator because so many things can be wrapped up in that one,” Hudgins said.

Evidence shows, Bell said, that policies to improve the health status of reproductive-age women positively impact birth outcomes and lead to healthier birth weight. She said the current conversation the state is having over whether to expand Medicaid coverage to low-income individuals is decisive for the health of future children.

“We currently have a policy debate before us as a state of whether or not we’re going to potentially take advantage of an opportunity that could potentially move the needle on that indicator for kids,” Bell said.

Growing up poor

On the downside, 25 percent of North Carolina kids were growing up in poverty in 2013, an increase from 20 percent in 2008. Fourteen percent live in high-poverty areas, an increase from 9 percent, outpacing the national average.

“Those are the kinds of communities that often lack resources that help promote healthy child development,” Bell said. “So those are kids that don’t have access often to high-quality schools; to good, nutritious foods; that may be exposed to higher rates of community violence.

Get notifications of new NC Health News stories to your newsfeed – “like” us on Facebook today!“All of those things have a really damaging effect on children during those key developmental periods of their life.”

Hudgins also expressed concern about the social determinants of health.

“How well children are doing out in their community has a lot of weight on how well they do for health and other indicators as well,” she said. “We really pay attention to the whole picture and the entire community.”

Since the legislature let the earned income tax credit and the child tax credit expire and took away child-care subsidies, low-income families aren’t getting the same boost they used to, Hudgins said.

The state is still reaping the long-term benefits of earlier investments, Bell said, as shown by improvements in the health and education sectors.

But if North Carolina wants to keep seeing these returns, she said, they need to invest in evidence-based policies that mitigate the negative effects of poverty.

In the classroom

Having health insurance and receiving access to high-quality preventative care means kids are in classrooms instead of home sick, Bell said, so investing in health leads to positive education outcomes.

The number of fourth-graders not proficient in reading dropped to 65 percent from 71 percent in 2007, the fifth-largest drop in the U.S.

“Obviously, 65 percent is too high and we need to keep cutting that,” Bell said. “But we’re moving in the right direction and outpacing many of our peers.”

According to research, reading and math proficiency in elementary and middle school are linked to early-education quality. But Bell said the state isn’t investing in early education like it used to.

“In the past, our state was quite a leader in early education, and really a national and international model, and made significant investments in those areas,” she said.

But in recent years, she said, North Carolina has cut money toward programs such as NC Pre-K and Smart Start, and thus low-income families haven’t had the same access to these early-learning opportunities that they did before the recession.

The rate of children not attending preschool increased to 58 percent, a 4-point jump from 2009.

Source: Report: N.C. Kids Poorer, but do Better in Health and School.