Happy December!

As the year winds down, many of us find ourselves pausing to look back at what went well, what stretched us, and what we hope to build in the year ahead. At NC Child, we do the same. And in my role as our quantitative research and data analyst, that reflection often begins with the numbers: Where are North Carolina’s children thriving? Where are they struggling? And how can strong policy close the gap?

Youth mental health is one issue that always brings me back to the “why” of this work. Before joining NC Child, I studied Neurobiology and Psychology at NC State with early plans to become a Child & Adolescent Psychiatrist. I spent years at UNC Children’s, working across nearly every specialty with kids ranging from newborns in bassinets to teens preparing for college.

In those hallways, I met countless young people carrying invisible burdens. Some trusted me enough to share their mental health struggles directly. I saw moments when timely intervention changed a child’s trajectory.

And I saw moments when help came too late.

Ultimately, I chose a different path than medical school, but the stories I carry from that time shape me every day. They remind me that the pain many children experience is real. It’s urgent. And it will not be resolved on its own. It requires all of us—advocates, policymakers, caregivers, and community partners—to shine a light on what our young people are facing and to fight for the support they deserve.

Youth Suicide in North Carolina: What the Numbers Are Telling Us

The numbers make one thing painfully clear: more young people in North Carolina are struggling, and some are reaching a point of deep crisis.

For children ages 0–17, suicide rates have risen from 1.5 per 100,000 in 2012 to 2.5 in 2023. Even when we look at the data in multi-year blocks so that we are not overstating the importance of any one unusually bad year, the pattern holds. The rate climbed from 1.7 (2012–2017) to 2.3 (2018–2023), roughly a 30 percent increase over a decade.

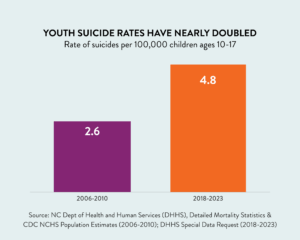

Among older youth ages 10–17, we found that suicide rates nearly doubled from 2.6 per 100,000 (2006-2010) to 4.8 (2019-2023) ¹

We hear the lived experience behind these numbers in nearly every conversation with teachers, school counselors, and parents. Middle- and high-schoolers talk about feeling “constantly anxious.” Teens describe the weight of juggling academics, jobs, family expectations, and friendships while also trying to keep up with the pressures of social media. Adults who work closely with youth say they’re seeing more depression, more hopelessness, and more moments when a child’s stress tips into crisis.

Behind every data point is a young person in real pain, along with families and schools working to find the support they need.

Local Stories Behind the Numbers

The statewide trend is strong, but the story varies across communities. Buncombe and Davidson counties both saw large, statistically significant increases in youth suicides over the past decade, while Franklin County saw a decline during the same period. Yet even where the data appears unchanged, youth mental health remains a top concern for all counties across the state. As the Child Health Report Card notes, “local School Health Advisory Councils ranked mental health as their number one priority for the past eight years.”

In Buncombe County, a 2023 report to the County Commissioners cited “the lack of a coordinated, county-wide effort focused on youth mental health and suicide” as a major reason progress has stalled. The 2024 update echoed those concerns and highlighted stigma as a persistent barrier for youth and families, especially in underserved communities.

These findings match what we heard directly from community members during a 2024 listening tour session held in Buncombe County. One county health worker told us:

“We’ve seen a steady increase in children experiencing social, emotional, [and] behavioral challenges… but the numbers and the severity of the behaviors is so worrisome.”

Our data does not yet include 2024, so it will not reflect any impacts of Hurricane Helene on mental health access or system strain.

Davidson County has raised similar alarms. Atrium Health’s 2024 Community Health Needs Assessment identified mental health — specifically depression and suicide — as the number one priority among residents, providers, and local leaders. There was no single explanation for why suicide rates have risen, but the shared recognition of the problem is an important starting point.

Franklin County’s experience, on the other hand, looks different. It was the only county we found with a statistically significant decrease in the youth suicide rate from 2012 to 2023. Local government resources highlight a range of counseling options for families, including at-home services for youth who may not otherwise be able to access care. While we cannot draw a direct line between these supports and the decline in suicides, the availability of care close to home may help create stronger conditions for young people to get the help they need.

The Pandemic Effect

Chatham County stands out when we compare the years directly before and after COVID. Before the pandemic, its youth suicide rate was effectively zero. Between 2020 and 2023, that rate rose to 8.3 per 100,000 youth ages 0–17. For older youth ages 10–17, the rate reached 13.2 per 100,000 during 2019–2023.

This growth in youth suicide rates in Chatham suggests that the increase may be connected to the intense stress and isolation many young people experienced during the pandemic. At the same time, the change does not meet the usual threshold for statistical significance, so it should be interpreted with caution. Even so, the pattern is notable and fits within a broader context of rising youth mental health needs.

Statewide, suicide rates among youth ages 0-17 also rose during COVID, from 1.9 per 100,000 (2017-2019) to 2.4 (2020-2023). For older youth ages 10–17, the rate reached 4.8 per 100,000 during 2019–2023. That increase is concerning, but it aligns with the long-term upward trend we have been tracking for more than a decade. Chatham County’s spike looks different. Its rise appears tied specifically to the pandemic years rather than to the statewide pattern, making it an important outlier to watch as more data becomes available.

What This Means for North Carolina

Across the state, the message is clear: young people need more support. NC Child & NCIOM’s 2025 Child Health Report Card shows that more than half of North Carolina children who needed mental health treatment in the past year could not get it.

Schools are doing what they can, but the need far outpaces the resources. Right now, there are 1,928 students for every school psychologist and 995 students for every school social worker in North Carolina. That’s nearly four times the recommended level. These shortages mean that schools are often forced to focus only on students in crisis, rather than providing early, preventive support.

What We Can Do

We can change the trajectory of youth suicides in North Carolina, but it’s going to take coordinated action. Here are a few things we can do to make a difference right now:

- Provide suicide prevention and mental health training for teachers (H578)

- The Jason Flatt Act (H578) currently awaits Senate committee approval. If passed, it would require schools to develop and implement a school-based mental health policy plan, including suicide prevention, intervention, and postvention protocols, steps for identifying and referring students at risk, and procedures for staff training and crisis response. All licensed school personnel would receive annual suicide prevention training as part of their already-existing professional development requirements.

- The Jason Flatt Act (H578) currently awaits Senate committee approval. If passed, it would require schools to develop and implement a school-based mental health policy plan, including suicide prevention, intervention, and postvention protocols, steps for identifying and referring students at risk, and procedures for staff training and crisis response. All licensed school personnel would receive annual suicide prevention training as part of their already-existing professional development requirements.

- Fully fund school-based mental health positions

- Every student deserves access to a counselor, psychologist, and social worker at their school. These licensed professionals provide essential services for our students and can make the difference between crisis and recovery.

To see whether how your county or school district is meeting students’ needs, check out our Mapping School-Based Mental Health Dashboard.

Moving Forward

We know that when communities invest in early prevention, when schools are staffed to meet kids where they are, and when stigma is replaced with open conversation, lives are saved.

Youth suicide is preventable. It takes all of us — Schools, parents, students, policymaker, and advocates — working together.

Yours in service,

Ashtin Crawford

Research and Data Analyst

¹ Rates are based on different data constructions: 2006–2010 calculated by NC Child using NCDHHS suicide deaths and CDC NCHS population estimates; 2019–2023 calculated by NCDHHS via special data request (population source may differ). Figures are not strictly comparable but represent the best available estimates.