Competition is such a deeply held American notion—we strive to be first, fastest, smartest, coolest, funniest—almost anything you can measure. If competition isn’t formally organized, it’s carried on with bumper stickers proclaiming our relationship to honor students, colleges we attended, or towns we live in.

Sometimes we take it personally if we, or our team, doesn’t win or show up well.

That’s exactly what we ought to do with new North Carolina data on the well-being of children in the recently released KIDS COUNT Data Book.

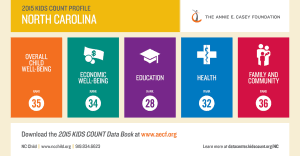

The Data Book provides state-by-state comparisons of 16 indicators of child well-being in four categories, telling a story about the well-being of North Carolina children relative to their peers across the country. Each year NC Child partners with the Annie E. Casey Foundation to release this data, and, we hope, to provoke a conversation about what it means to compete to have children grow up as healthy, well educated and economically secure adults.

While the state of Virginia ranks 14th in the nation for overall child well-being, North Carolina this year ranks 35th, among the worst performing states for Economic Well-Being (34th) and Family and Community (36th), and faring about mid-range for Education (28th) and Health (32nd).

No bumper sticker here

The story of child well-being in North Carolina is one of declining financial security for families, even as their children continue to make gains in education and health. Between the survey dates of 2008 and 2013:

- Child poverty rose 25 percent. Now one in four children lives in poverty, and North Carolina has the 11th highest child poverty rate in the country.

- One in three children lives in a family where the parents lack secure employment.

- One in three children lives in a family that struggles to afford the cost of housing.

- Racial and ethnic disparities in income and opportunity are widening. African American, American Indian and Latino children are twice as likely to live in poverty.

The explosion of children living in concentrated poverty is one of the most alarming new trends in the Data Book. In 2000, just 4 percent of North Carolina children lived in high poverty neighborhoods. Today 14 percent do.

The percentage of children in high-poverty areas has grown twice as fast here as in the nation. This means more of our children are growing up in neighborhoods that lack access to critical resources like fresh, nutritious foods, high-quality schools and safe, walkable spaces that encourage exercise and play.

Recent analysis shows where children live and the conditions in their neighborhoods (i.e. less segregation by income and race, lower levels of income inequality, better schools, lower rates of violent crime, and a larger share of two-parent households) shape children’s long-term earnings, life expectancy, academic achievement and more.

Losing that kind of competition is something we ought to take personally as North Carolinians, with our tradition of building social structures like schools, universities, parks and transportation systems that make economic life more vibrant. We know how to do this kind of work. We just need the will to do it.

Closer to the middle in health and education

The data is not all bad, because we have taken action in the past to invest in children’s health and education. Thanks to initiatives like state support of NC Health Choice and Medicaid, the number of uninsured children is at the lowest level in state history, with 94 percent of North Carolina children insured.

We have to ask ourselves now: are we doing enough to keep up the momentum? I fear we are not.

“Where all the children are above average”

Radio storyteller Garrison Keillor says his fictional hometown of Lake Woebegone, Minnesota is “where all the women are strong, all the men are good-looking, and all the children are above average.” We don’t know where he gets his data on the men and women, but he’s got the right notion about the children.

Minnesota tops the list for overall child well-being, followed by New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Iowa, and Vermont. These states are not inherently better places to be or raise a child than North Carolina. Instead, policymakers, advocates and local communities have worked together to implement policies and programs that strengthen the well-being of children and their families.

These states don’t have secret programs or money machines. They’ve made children’s health and education and the economic and world around them, a priority. We could do the same kinds of things, and we have done them in the past, like enacting the Earned Income Tax Credit which has lifted thousands of North Carolina children out of poverty.

If we wanted to seriously compete as a state, we would need to make investments in programs and policies that close racial and geographic gaps, enhance work supports to keep parents working and earning an adequate wage, and increase children’s capacity to acquire skills to be successful in the 21st century economy.

And we need to come up with a bumper sticker for that.